By Dylan Scott, Vox.com

For many of you, it probably feels as though it’s long past time we got to thinking about how to reopen society. We learned today that some of the public officials who will make those decisions have started doing so. Governors across the mid-Atlantic, from New England to Delaware, are working on a “regional reopening plan.” And the West Coast’s three governors announced shared principles that will guide their decisions to reopen. This is no time to celebrate, not with 22,000 people dead and more sadly to come, but life after coronavirus is becoming less of a hypothetical by the day.

There are a few important scientific questions and pursuits that will underline those decisions. Many of these are within our control — testing, treatments, etc. — but there is one critical issue that is not: immunity to the coronavirus itself.

Let’s start with this first group before turning to the second. On mass testing, as my colleague German Lopez wrote last week, America has still not achieved the level of testing we would like. In our latest update, by my and Rani Molla’s count, the US was still testing half as many people per capita as Italy (one of Europe’s epicenters) and Germany (a model for rapid testing).

Our efforts would also be aided by serological testing, which tells us whether somebody has built up antibodies to resist the coronavirus — and is therefore more likely to be immune. Though serological testing has its limits (more on that later), Vox’s Umair Irfan covered the major implications of what that kind of testing could do at length earlier this month:

In patients who have recovered from Covid-19 or may have carried the virus without realizing it, a serological test can show who carries antibodies, even if the virus is no longer present. Antibodies are proteins that help the immune system identify and eliminate threats. Once they’re made, they help the body neutralize future infections from the same threat.

Establishing who is immune is important for figuring out who can safely return to work. For example, health workers are facing staffing shortages as Covid-19 spreads through their ranks, and serological tests may soon become necessary to keep hospitals and clinics running.

These tests are also a forensic tool, tracing the spread of the virus through a population. This can solve some of the unknowns of the Covid-19 outbreak and help scientists get ahead of the next pandemic. Countries like China and Singapore have already used serological tests for contact tracing to see how the virus has spread.

And, as Matt Yglesias reported over the weekend, every American will be able to get an antibody test for free.

There are other relevant and related threads here. Can we come up with a reliable clinical regimen to treat Covid-19 in people who get infected? (More from Umair.) Can we eventually develop a vaccine? (A comprehensive guide from Umair, Brian Resnick, and Julia Belluz is here.)

Oh, and don’t forget, we still don’t know how the coronavirus will behave when the weather changes.

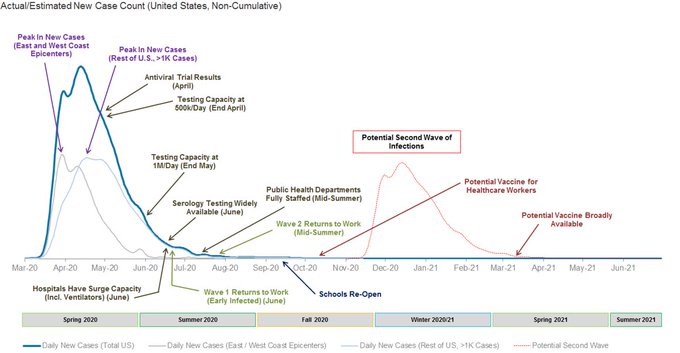

If you want to know how all these things might merge together to answer the question of “When will life start going back to normal?”, Robin Wigglesworth at the Financial Times shared this graphic on Twitter, crediting it to Morgan Stanley:

Morgan Stanley: “While we understand the desire for optimism, we also caution that the US outbreak is far from over. Recovering from this acute period in the outbreak is just the beginning and not the end. We believe the path to re-opening the economy is going to be long.”

I wouldn’t take that timeline to the bank, by any means, but it’s useful in illustrating how smart people whose money will depend on a functioning economy — and healthy consumers — are thinking about it.

Many of these things — mass testing, antibody testing, cures, vaccines, ending social distancing — are within human control, at least to some degree. But there is one big variable that is left only to nature: immunity itself.

Most laypeople, including me, might think of immunity in pretty simple terms: You get infected by a virus, your body builds up antibodies to fight it off, and you are now immune from the virus because you have those antibodies.

But it’s not so simple. Immunity is a fickle science, as epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch lays out in a must-read op-ed for the New York Times:

Immunity after any infection can range from lifelong and complete to nearly nonexistent. So far, however, only the first glimmers of data are available about immunity to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes Covid-19.

What can scientists, and the decision makers who rely on science to inform policies, do in such a situation? The best approach is to construct a conceptual model — a set of assumptions about how immunity might work — based on current knowledge of the immune system and information about related viruses, and then identify how each aspect of that model might be wrong, how one would know and what the implications would be. Next, scientists should set out to work to improve this understanding with observation and experiment.

Lipsitch is a very accessible writer, so I’d encourage you to read his thoughts in full. But these were my main takeaways from his piece:

- Coronaviruses, the family of viruses of which the SARS-Cov-2 pathogen that causes Covid-19 is a member, have a “complicated” record with that simplified version of immunity I gave above

- Studies from the 1970s and 1990s that examined how long an infected person’s immunity to other coronaviruses persisted found that, in general, most people did maintain some level of immunity — it was strongest for the exact same strain, less so for separate but related strains

- Research from the SARS and MERS outbreaks this century found people maintained antibodies from their infections for two to three years, though their level of resistance was starting to taper by the end of that period

- Lipsitch himself and other researchers have projected for other seasonal coronaviruses that immunity is likely to last for about a year

- Though some have worried about reinfection, given cases of people testing positive then negative then positive, scientists believe other explanations are just as likely (that these results are either an errant test in the middle of a single case or the same infection receded and then surged back)

- What we are hoping to build up is herd immunity. The more people who are immune, the less likely an infected person will give the virus to a vulnerable person, thereby slowing the pandemic’s spread.

But to bring us full circle, it’s difficult to ascertain herd immunity without widespread diagnostic and serological testing. The faster we can ramp up those capabilities, the more information we will have to make smart decisions about reopening society.

”Getting a handle on this fast is extremely important: Not only to estimate the extent of herd immunity but also to figure out whether some people can re-enter society safely, without becoming infected again or serving as a vector, and spreading the virus to others,” Lipsitch writes. “Central to this effort will be figuring out how long protection lasts.”

The questions about immunity are clear. Now we need to find the answers. Thankfully, the brightest minds are already hard at work to do exactly that.

By Dylan Scott, Vox.com

{Matzav.com}

Recent comments